Music

Music

1 Composer, 2 Centuries, Many Picks

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI, ALLAN KOZINN, STEVE SMITH and VIVIEN SCHWEITZER

Published: May 27, 2010

The classical music world, embarked on a bicentennial tour through the Romantic era, is just now preoccupied with the melancholic master Frédéric Chopin, born near Warsaw in 1810. Beloved by pianists for his abundant legacy, he is cherished by countless others for the teeming worlds of color and emotion he conjured. The classical music critics of The New York Times have combed through the many recordings devoted to Chopin and selected their favorites.

Anthony Tommasini

Anthony Tommasini

HOROWITZ PLAYS CHOPIN, VOL. 1 Vladimir Horowitz, pianist (RCA Gold Seal 7752-2-RG; CD).

MAZURKAS Arthur Rubinstein, pianist (RCA Red Seal 09026 63050-2; two CDs).

PIANO CONCERTOS NOS. 1, 2 Krystian Zimerman, pianist and conductor; Polish Festival Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon 459 684; two CDs).

ÉTUDES Murray Perahia, pianist (Sony Classical SK 61885; CD).

CHOPIN: THE COMPLETE RECORDINGS Dinu Lipatti, pianist (EMI Classics 5 86826-2; two CDs).

FOR the most part Vladimir Horowitz is not among my preferred Chopin pianists. His performances, though always brilliant, tend to be quirky. But once in a while he nailed a piece, as with Chopin’s Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise, recorded in New York in 1945, one of the most astonishing piano recordings ever made.

Though perhaps not top-drawer Chopin, this piece is a knockout. In the opening andante, a tender, songful melody is spun over a rippling accompaniment. Then, with a fanfare flourish of leaping chords, the piece breaks into an exuberant, shamelessly showy polonaise. Horowitz gives an uncannily articulate and beguiling performance, dispatching the right-hand runs with breathtaking fleetness and delicacy, and lending bounce and crispness to the dancing accompaniment. The way he will gently nudge a crucial left-hand note to anticipate some harmonic turning point is awesome.

Now and then he makes a tiny slip. Clearly, he did not care. He knew listeners would be bowled over. The performance has been reissued many times, here in a release that also offers Horowitz in various live Chopin performances, all fascinating, recorded between 1979 and 1982.

The pianist who has won the broadest consensus for his exemplary Chopin is probably Arthur Rubinstein. He emerged when the use of expressive rubato and Romantic liberties in Chopin was rampant. In that context he was a model of refinement and taste, with no loss of rhapsodic fancy and imagination. You can trust him in any Chopin. And as a proud Polish artist playing Chopin’s mazurkas, which evoked a Polish dance form, he was unrivaled. I especially love his later recordings of the 51 Mazurkas, made in 1965 and 1966, when he was nearly 80. Even in the sprightly mazurkas his playing is subtly melancholic and mystical.

The pianist who has won the broadest consensus for his exemplary Chopin is probably Arthur Rubinstein. He emerged when the use of expressive rubato and Romantic liberties in Chopin was rampant. In that context he was a model of refinement and taste, with no loss of rhapsodic fancy and imagination. You can trust him in any Chopin. And as a proud Polish artist playing Chopin’s mazurkas, which evoked a Polish dance form, he was unrivaled. I especially love his later recordings of the 51 Mazurkas, made in 1965 and 1966, when he was nearly 80. Even in the sprightly mazurkas his playing is subtly melancholic and mystical.

A pianist who can play the 24 Chopin Études can play anything. People may not think of Murray Perahia, that poet of the keyboard, as a dazzling virtuoso type. But he conquers the études on his stunning 2002 release, while bringing out the musical riches of these milestone piano pieces.

More than a decade ago the formidable Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman, tired of hearing everyone trash the orchestrations of Chopin’s two piano concertos, decided to do something about it. He formed a special touring ensemble of excellent younger musicians, the Polish Festival Orchestra, and worked in detail to uncover the complexities and inventive touches in Chopin’s orchestra writing. Playing and conducting from the keyboard, he performed the two concertos on tour and recorded them in 1999. The performances are revelations. Here again Mr. Zimerman shows himself to be one of the finest pianists of our day.

Then there is the magnificent Dinu Lipatti, who was just building his recorded legacy when he died of cancer in 1950, at 33. A musician of uncommon sensitivity and intelligence, he was an exquisite Chopin player. His complete Chopin recordings have been issued in a two-disc set, including the First Piano Concerto, the Third Sonata, the 14 waltzes, selected nocturnes and mazurkas, and an incomparable account of the deceptively complex Barcarolle.

Allan Kozinn

PRELUDES Alexandre Tharaud, pianist (Harmonia Mundi HMC 901982; CD).

PRELUDES Alexandre Tharaud, pianist (Harmonia Mundi HMC 901982; CD).

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1, SOLO PIANO WORKS Emanuel Ax, pianist; Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, conducted by Charles Mackerras (Sony Classical SK 60771; CD).

BALLADES, BARCAROLLE, FANTAISIE Jorge Bolet, pianist (Decca 417 651-2; CD).

PIANO SONATA NO. 3, OTHER WORKS Yundi Li, pianist (Deutsche Grammophon 471 479; CD).

ÉTUDES Vladimir Ashkenazy, pianist (Decca 414 127; CD).

IF you think that works as familiar as the Chopin Preludes cannot sound fresh, compelling, even revolutionary, listen to the live-wire traversal by the French pianist Alexandre Tharaud. Inspired at least partly by Schumann’s description of the Opus 28 Preludes as “eagles’ pinions, wild and motley pell-mell,” Mr. Tharaud gives each of these little pieces a painterly and often dramatic reshaping, toying with tempos and coloration, and reconceiving the set as a sort of Chopin-esque “Pictures at an Exhibition.”

Emanuel Ax is hardly an early-musicker, and the Chopin concertos are hardly early music. But Mr. Ax’s performance of the First Concerto on a restored 1851 Érard piano with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment combines the textural transparency that makes period-instrument recordings so appealingly fresh and the deeply considered, poetic phrasing that has always characterized Mr. Ax’s Chopin. The sound of the Érard is closer to that of the modern piano than to that of the fortepiano, but it has a distinctive, slightly glassine tone that Mr. Ax uses to the advantage of both the delicate and the assertive extremes of the concerto, and the less frequently heard Variations on “Là ci darem la mano.”

Jorge Bolet embraced the grand Romantic approach to pianism that prevailed in the first half of the 20th century, but he tempered the impulse toward showy display with a probing interpretive style that kept his performances from devolving into empty virtuosity. His 1986 recording of the Ballades, the Barcarolle and the Fantaisie is a superb example of his Chopin playing: pensive and powerful, with an inarguable ebb and flow. It also beautifully captures the Bolet sound, with its rich basses and crystalline trebles.

Among the many dazzling accounts of the Études, I find myself returning most often to Vladimir Ashkenazy’s traversal. Rich in coloristic variety and hard-driven as these technique-testing works must be, Mr. Ashkenazy’s performances are passionate and fiery, but an important part of this pianist’s appeal has always been that finger power is only half the story; you always have the sense of a keen intellect at work, even in pieces (like the “Black Keys” and “Winter Wind” Études) that may appear to exert a purely visceral appeal.

Many of the qualities that distinguish Mr. Ashkenazy’s performances can be found in Yundi Li’s Chopin as well. This young Chinese pianist (now calling himself simply Yundi) is in some ways the anti-Lang Lang: his technique is as formidable as that of his superstar countryman (and in many ways more reliable), and he is by no means averse to pointing up the drama in this music. But as his shapely performances of the Sonata No. 3 and several shorter works show, he is more intent on finding the music’s poetry than its attention-grabbing (and ovation-inducing) sparkle.

Steve Smith

Steve Smith

BALLADES, SCHERZOS Arthur Rubinstein, pianist (RCA Red Seal 82876 61396-2; CD).

NOCTURNES Ivan Moravec, pianist (Nonesuch 9 79233 2; two CDs)

THE LEGENDARY 1965 RECORDING Martha Argerich, pianist (EMI Classics 5 56805 2; CD).

WALTZES Alexandre Tharaud, pianist (Harmonia Mundi HMC 901927; CD).

BALLADES, OTHER WORKS Piotr Anderszewski, pianist (Virgin Classics 6 86370 2; CD).

CHOOSING just five recordings to represent most composers poses a challenge, but doing so for Chopin is especially daunting. His music, so fastidiously wrought and emotionally generous, rewards faithful interpretations while also embracing idiosyncratic approaches; you’re spoiled for choice across a vast temperamental range. But if one thing is clear, it is that any collection must include at least one recording by Arthur Rubinstein, whose keen insights were shaped by a lifelong association with Chopin’s music.

With dozens of options available, I am especially partial to Rubinstein’s magisterial 1959 recordings of the Ballades and Scherzos, made when he was 72. Even this late in Rubinstein’s life his technical capacity holds up. Racing lines in the Scherzo No. 1 will leave you breathless. An overall sense of consideration and rightness permeates this session, and John Pfeiffer’s recording is outstandingly lifelike in a 2004 hybrid Super Audio CD edition, even when played on conventional stereo equipment.

Much the same could be said of Ivan Moravec’s set of the Nocturnes, taped in 1965 by E. Alan Silver for the Connoisseur Society label and issued on CD by Nonesuch in 1991. Even by modern standards the recorded sound is astonishing; you may have to adjust to Mr. Moravec’s breathing and other extraneous sounds. But his extraordinary dynamic shading and gracious shaping of each gemlike work lift his account above a crowded field: truly, this is an essential document.

A contractual conflict long prevented the release of the Chopin recital that the tempestuous Argentine pianist Martha Argerich made for EMI in 1965, shortly after she won first prize at the International Frédéric Chopin Piano Competition at 24. Finally issued in 1999, the CD captures Ms. Argerich’s white-hot intensity and personalized approach, with ample tenderness and reflection balancing the dash and brio. The sound is overly reverberant, and some climaxes turn brittle; still, Ms. Argerich’s dazzling technique and penetrating engagement sweep away any reservations.

Among complete recordings of Chopin’s Waltzes, Dinu Lipatti’s 1950 EMI account has reigned supreme for decades because of its polish and magnanimity. But the French pianist Alexandre Tharaud also has much to say in this music, a point made in his 2006 Harmonia Mundi collection. Mr. Tharaud is fastidious and flexible, yet what impresses most about his interpretation is an inner glow that illuminates the wistful, introspective qualities in these elegant miniatures and extends to the concluding work, Mompou’s tender “Valse-Évocation (Variations sur un Thème de Chopin).”

A 2004 recital disc by Piotr Anderszewski might not suit every taste, given the broad tempos and elastic phrasing this Polish-Hungarian pianist adopts in seven mazurkas, two ballades and two polonaises. For me Mr. Anderszewski’s attention to detail and nuance is compelling; a sense of intensely personal identification with each piece is inescapable and utterly sublime.

Vivien Schweitzer

Vivien Schweitzer

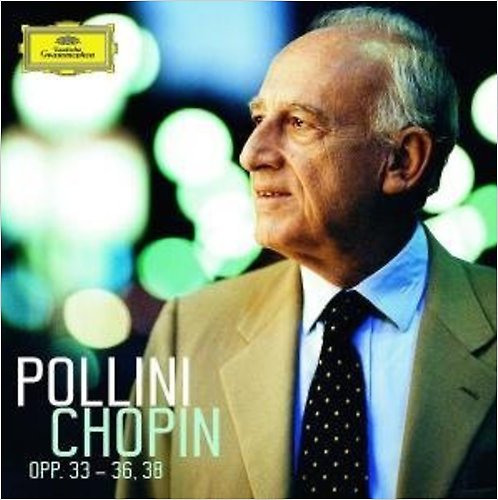

PIANO SONATA NO. 2, OTHER WORKS Maurizio Pollini, pianist (Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 8046; CD).

PIANO SONATA NO. 3, OTHER WORKS Ingrid Fliter, pianist (EMI Classics 5 14899 2; CD).

ARGERICH PLAYS CHOPIN Martha Argerich, pianist (Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 7557; CD).

EVGENY KISSIN PLAYS CHOPIN Evgeny Kissin, pianist (RCA Red Seal 82876 68668-2; CD).

CELLO SONATA, PIANO SONATA NO. 3, OTHER WORKS Maria João Pires, pianist; Pavel Gomziakov, cellist (Deutsche Grammophon 289 477 7483; two CDs).

THE Italian pianist Maurizio Pollini has been an important Chopin performer since he won the International Frédéric Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1960. As recent recitals and this disc demonstrate, his prowess as an unsentimental, powerful interpreter is not waning. This compilation includes a riveting rendition of the Ballade No. 2, whose gentle opening section explodes with dazzling force into the turbulent second part. Also included are a potent performance of the Sonata No. 2 and elegant renditions of the Four Mazurkas (Op. 33) and Three Waltzes (Op. 34).

The Argentine pianist Ingrid Fliter has been a welcome addition to the roster of Chopin performers since she came into the spotlight in 2006, when she won the Gilmore Artist Award. Her singing lines, warm touch, probing musicality and impressive technique are highlighted in richly hued performances of the Sonata No. 3 and the Ballade No. 4. Ms. Fliter also offers distinctive interpretations of the Opus 59 Mazurkas, the Opus 64 Waltzes and the Grande Valse Brillante, and a poetic rendition of the Barcarolle in F sharp.

Ms. Fliter had as a mentor her brilliant Argentine colleague Martha Argerich. The Argerich disc here features some works, including the Ballade No. 1, that Ms. Argerich has not recorded elsewhere. The surface noise of these performances, taken from German radio recordings made in Berlin and Cologne in 1959 and 1967, though a slight irritant, doesn’t detract too much from Ms. Argerich’s terrific playing. Then as now, her explosive technique and fiery musicality were always impressive, revealed in selections including the Étude in C sharp minor, which unfolds in a dazzling whirlwind. But profundity is never sacrificed for virtuosity, as demonstrated in memorable interpretations of eight mazurkas, the Sonata No. 3 and two nocturnes.

Evgeny Kissin first made his name playing Chopin at 12, receiving acclaim for a Chopin concert recorded live in Moscow. His disc here, recorded live in 2004 at the Verbier Festival in Switzerland, illustrates a continuing affinity with the composer. Mr. Kissin performs four polonaises and four impromptus with his customary crystalline technique, singing tone and generous rubato.

Maria João Pires, the Brazilian pianist, focuses on works from the final years of Chopin’s relatively short life in a captivating recent two-disc release. The late-period Chopin represented includes the Sonata No. 3, with an introspective, wistful reading of the Largo, and two nocturnes, the Opus 59 and Opus 63 Mazurkas and the Opus 64 Waltzes in deeply musical interpretations. Chopin wrote almost exclusively for piano, but his catalog also includes the G minor Sonata for Cello and Piano, evocatively rendered here with the cellist Pavel Gomziakov.